Frank Deford, often considered the finest sportswriter of his generation for his detailed psychological profiles of athletes and coaches, who also won acclaim for his novels, his television and radio commentaries and for a heartfelt book about his daughter’s struggle with cystic fibrosis, died May 28 at his home in Key West, Fla. He was 78.

He had been treated recently for pneumonia, but the immediate cause of death was unknown, said his wife, Carol Deford.

Mr. Deford (pronounced duh-FORD) joined Sports Illustrated in 1962 and soon emerged as the most accomplished stylist on sportswriting’s brightest stage. He gained access to locker rooms and to the innermost thoughts of the world’s most famous athletes, yet many of his most memorable stories were about the forgotten figures in sports history.

In the 1960s, Mr. Deford wrote profiles of Princeton basketball star Bill Bradley and Boston Bruins rookie Bobby Orr that went beyond the locker room and revealed a humanity and even a spiritual depth in his subjects. His stories, along with those of other Sports Illustrated writers including Dan Jenkins and Mark Kram, helped raise sportswriting from the daily chronicle of victory and defeat to something with more literary ambition.

Tall and distinguished-looking, with a pencil mustache, Mr. Deford "looked like a movie star and dressed the part,” author Michael MacCambridge observed in "The Franchise: A History of Sports Illustrated Magazine.” Mr. Deford became "the anchor of the magazine, the writer around whom the rest of the issue was built,” MacCambridge added. "His prose was a graceful mixture of storytelling and subtle (sometimes not so subtle) psychoanalysis.”

Frank Deford receiving the National Humanities Medal from President Barack Obama during a White House ceremony in 2013. (Carolyn Kaster/AP)

Frank Deford receiving the National Humanities Medal from President Barack Obama during a White House ceremony in 2013. (Carolyn Kaster/AP) Mr. Deford captured the determined drive of tennis stars Arthur Ashe and Jimmy Connors and wrote a searching profile (and later a biography) of Bill Tilden, a 1920s tennis champion haunted by a secret gay life.

"He was the proudest of men and the saddest,” Mr. Deford wrote about Tilden, "but never so happy as when he carried his rackets into the limelight or walked into a room and took it over.”

In 1984, Mr. Deford wrote about a little-known Mississippi football coach, "the toughest coach of them all,” who was "so tough he had to have two tough nicknames, Bull and Cyclone, and his name was usually recorded this way: Coach Bob "Bull” "Cyclone” Sullivan.”

By then, Mr. Deford "had become an institution,” MacCambridge wrote, "the biggest name at the magazine, and one of the most emulated, respected, eagerly read writers in the country.” He was named sportswriter of the year by the National Association of Sportswriters and Sportscasters six times.

For Mr. Deford, it wan’t enough to present in-depth profiles of familiar names, such as coaches Paul "Bear” Bryant and Bobby Knight. He sought to grasp how sports were an inescapable part of the American soul, an emblem of loyalty, aspiration and, all too often, heartbreak.

In a 1985 feature, "The Boxer and the Blonde,” Mr. Deford recounted the saga of a 1941 heavyweight fight between the scrappy, undersized Billy Conn and the unbeatable champion, Joe Louis. But it was also a love story, as the title suggests, set in the flickering twilight glow of prewar America.

After 12 rounds at the Polo Grounds in New York, Conn was leading Louis and seemed assured of victory in what would have been a remarkable upset. Conn was knocked out in the 13th round.

"This was the best it had ever been and ever would be, the twelfth and thirteenth rounds of Louis and Conn on a warm night in New York just before the world went to hell,” Mr. Deford wrote. "The people were standing and cheering for Conn, but it was really for the sport and for the moment and for themselves that they cheered. They could be a part of it . . . and it can’t ever get any better. This was such a time in the history of games.”

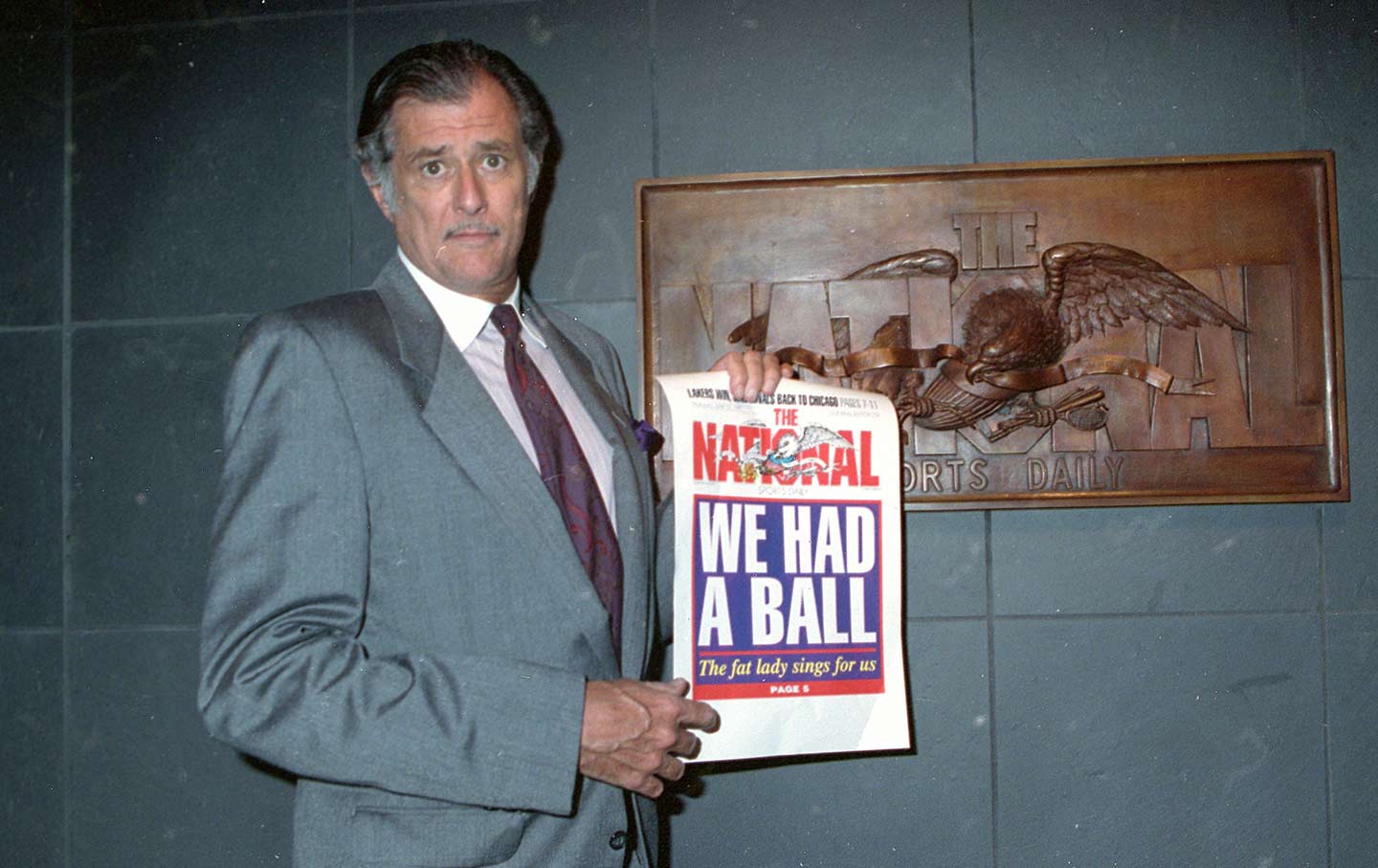

Mr. Deford left Sports Illustrated in 1989 to launch The National, a daily sports newspaper that folded 18 months later. Since the early 1980s, he had been a regular on the airwaves, often appearing on NBC, ESPN, HBO’s "Real Sports,” Miller Lite commercials and, for 37 years, as a weekly commentator on NPR.

His farewell radio essay was heard on NPR earlier this month.

Mr. Deford was often asked what the most impressive feat he had ever seen an athlete perform. In his 2012 memoir, "Over Time,” he wrote that it came on a visit to South Africa in the 1970s with Ashe, the African American tennis star.

Ashe agreed to go to a white college to debate the South African system of apartheid with white students.

"In your heart, do you think it’s right?” Ashe asked.

"The three students dropped their eyes,” Mr. Deford wrote. "I’ve never yet seen another athlete throw a touchdown pass or hit a home run or score a goal that was as impressive as what Arthur Ashe did that afternoon.”

Benjamin Franklin Deford III was born Dec. 16, 1938, in Baltimore. His father was a businessman.

Mr. Deford began writing as a schoolboy, but he was also a 6-foot-4 basketball star in high school. At Princeton University, he gave up the game after the coach told him, "Deford, you write basketball better than you play it.”

He was suspended for one year at Princeton after being caught with a girl in his room and missed another year while serving in the military. He was editor of the campus newspaper and skipped his graduation ceremony in 1962 to start work at Sports Illustrated.

After the National went defunct, Mr. Deford wrote for Newsweek and Vanity Fair and became a reporter on HBO’s "Real Sports With Bryant Gumbel.” He returned to Sports Illustrated as a contributor in 1998.

At a White House ceremony in 2013, President Barack Obama presented Mr. Deford with the National Humanities Medal, the first time a sportswriter had received the award.

Survivors include his wife of 51 years, the former Carol Penner of Key West and Manhattan; two children, Christian Deford of Manhattan and Scarlet Crawford of Stone Ridge, N.Y.; two brothers; and two grandchildren.

In recent months, Mr. Deford had completed a novel that is expected to be published later in the year.

Among his 18 books, he wrote 10 novels, including "Everybody’s All-American,” which was the basis of a 1988 feature film starring Dennis Quaid and Jessica Lange.

Mr. Deford’s most personal book, "Alex: The Life of a Child” (1983), was about his daughter Alexandra. The book became a made-for-TV movie in 1986. In the book, Mr. Deford wrote of the inevitable moment when his daughter asked if she was going to die.

" ‘Well, sure,’ I said,” Mr. Deford wrote, "as casual as I could be myself. I’d been prepared for this for a long time. ‘You’ll die sometime. But I’ll die, too. If there’s one thing we all do, it’s die.’

" ‘But you’ll be real old,’ she said. " ‘Not necessarily. I mean, I could die in an accident anytime.’

"Alex threw her arms around my neck. ‘Oh, my little Daddy, that would be so unfair.’

‘Unfair?’ I said. Unfair is just what she said.

" ‘You don’t have a disease, Daddy. You shouldn’t have to die till you’re real old.’ ”

Alexandra died in January 1980 at the age of 8.

Frank Deford was a part of my family lore years before I was

born. My father was a student reporter in 1958 and had a young running

buddy from Baltimore named Frank Deford.

Frank Deford was a part of my family lore years before I was

born. My father was a student reporter in 1958 and had a young running

buddy from Baltimore named Frank Deford.